According to new polling, the percentage of six Arab publics who believe America has had a positive role in the war amounts to just 7%.

Throughout the fifteen years that following the 2011 withdrawal from Iraq, each American presidential administration has experienced domestic calls to leave the Middle East. However, each time these voices grew louder, a new regional variable emerged that compelled the American administration to return to its traditional role dictated by urgent strategic security and economic interests.

After the withdrawal from Iraq, a strategic vacuum led to the emergence of and fight against ISIS, with the deaths of thousands both locally and internationally, and millions from the region displaced. The U.S. military was forced to return to the region to contribute to the efforts to eliminate ISIS. When this goal was declared completed, new regional threats emerged in the form of Iran and its weapons, which threatened not only America’s allies but also the free flow of global oil supplies. While the Biden administration thought this problem could be resolved through a package of incentives and agreements with Iran, the war in Gaza has emerged to confirm once again the error of U.S. assessments that contend that this region is no longer important to America’s strategic interests.

According to the third section of the U.S. National Security Strategy document signed by President Biden in October 2022, America’s top priority on the global stage is to surpass China, followed by limiting Russia’s influence. The national security priorities also include combating terrorism in the Middle East.

When it comes to the Middle East, key to all of these missions is the regional public perception of the United States’ role and its intentions there. The data from a recent public opinion poll conducted by the independent research group IIACSS and its partners in the region—polling nationally representative samples in Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, and Palestine during the period October 17-29, 2023–indicate that right now, America is losing ground in ways that can impact all three priorities identified in the National Security Strategy document.

Because of U.S. support for Israel, America’s trust and influence among Arabs in the region has reached its lowest point historically, while support for its competitors and strategic opponents—China, Russia, and Iran—has increased. Meanwhile, a worrying concurrent indicator in the polling suggests a growth in attitudes that have helped fuel past ISIS, Al-Qaeda, or even militia terrorism recruitment.

In short, among these six key Arab publics, America is losing compared to its opponents because of the war in Gaza. The percentage of Arabs who believe America has a positive role in the war amounts only to 7%, with figures as low as 2% in countries like Jordan. By contrast, the percentage of Arabs who say that China has a positive role in the conflict included 46% in Egypt, 34% in Iraq, and 27% in Jordan. Positive views of Russia are even higher; the percentage of those who believe that Russia has a positive influence neared half—averaging 47% among the publics surveyed (except in Palestine).

Moreover, it seems that Iran has been a major beneficiary of this war. On average, percentage of those who say that it had a positive impact in the war is 40%, compared to 21% those who say that it has anegative impact. In countries such as Egypt and Syria, the percentage who say that Iran has a positive influence in Gaza is even higher, reaching 50% and 52% respectively.

Such views are underpinned by a near total lack of trust in the United States and its intentions. Only 3% of Jordanian respondents say they trust America, compared to 24-25% who say the same for Russia and China. In Iraq, only 7% of respondents say they trust America, compared to 33% for Iran and China, and 36% for Russia. And as for Egypt, trust in America amounts to only 9%, compared to 51% for Russia andIran, along with 47% for China. These numbers are the lowest favorability ratings for America in the more than twenty years that we have spent researching public opinion in the region. According to a study by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in 2020, even at the lowest ebb of American favorability in the region, the negative evaluation of America’s policies towards Palestine did not drop below 19%.

It is clear that the way the United States has handled the war in Gaza has cost it what remained of a perception of credibility and neutrality among a proportion of these Arab publics. Those who follow what is published in the Arab media and social media platforms likewise realize how great America’s loss of soft power has been in the region over the past month. The United States, which has invested trillions of dollars in the Middle East over the course of a century and expended significant blood and sweat in the region, is in danger of the return on that investment being significantly diminished because of this conflict.

Widespread perceptions of the Gaza War also provide a service to terrorism in the region. The first principle that we learned from research for a recently published book about the life cycle of ISIS in Iraq is that to effectively combat terrorism, it is necessary to win the battle of hearts and minds among the population. Winning this battle ensures that terrorists are deprived of any popular support, in addition to helping to mobilize public opinion to fight them.

In the first interview I conducted in a Baghdad prison with one of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s senior aides years ago, he asked me: Have you wondered why ISIS was able to recruit thousands of fighters from all over the world in a short amount of time and occupy a vast area of Syria and Iraq in a short period, while Al Qaeda could not? Why can Al-Qaeda, which is the intellectual incubator of ISIS and older than ISIS in experience and expertise, attract only a limited number of fighters?

When I asked for his answer, he suggested that it was because ISIS—in contrast to Al-Qaeda—simply does not care about the ideological background and religious faith of its fighters. We (he said) focus our recruitment efforts on every person who has a reason to fight America, the West, or the regime in Iraq or Syria, regardless of how religious they are. ISIS is like a bus that stops at various stations and says, “We are going to fight all these enemies (the West and other regimes in the region). Whoever wants to fight with us should take the bus.” The basic idea, then, is that it is us versus them.

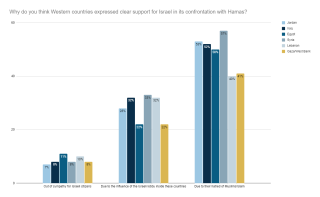

Given this context, if America prioritizes combating terrorism in the region as it repeatedly declares, then the Arab public opinion poll numbers bear nothing but unpleasant news for this effort. In our recent survey, when asked about the reasons for America and the West’s support of Israel, just an average of 8% answered that the reason was to defend civilians who were kidnapped or killed by Hamas on October 7. Half—the significant plurality choice out of three options—said that the reason the West supports Israel is because they hate Islam and Muslims. About 30% answered that the reason was the strength of the Israeli lobby. The majority of Arabs see the West’s support for Israel’s war against Hamas as support for a war against them.

One of the most important secrets of American soft power in the face of its competitors is the American model based on human rights, rejection of racism, and repudiation of the “law of the jungle” in international relations. Currently, this public opinion polling emphasizes that the overwhelming majority of respondents do not believe that these principles are being applied in the official American stance on the war in Gaza.

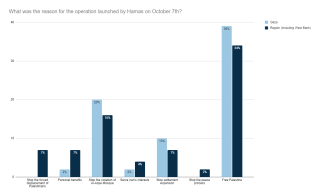

This is sobering information for Western and particularly American policymakers when they consider how the landscape of Arab public opinion has turned so decidedly against them. In essence, the majority of Arabs likely see the current conflict as akin to a new Crusade, not a fight against a terrorist organization—precisely the perception that extremists want Arabs to adopt in order to facilitate recruitment. This deep divide on the question of the war’s underlying conflict also relates to how Arab publics view Hamas’ October 7 attack. Whereas Western governments and publics tend to view Hamas’ attack as either designed to stop regional normalization with Israel, serve Iran’s goals in the region, or solidify its control in Gaza, only 13% of Arab respondents listed any of these theories as Hamas’ main intention. More than 60% instead chose liberating Palestine, stopping Israeli violations at Al-Aqsa Mosque, or halting settlements.

There are some silver linings—America still enjoys a fair degree of Arab trust (44%) in its ability to help the Palestinians if it wanted to. This attitude is a double-edged sword: when there is trust that an entity could address an issue but does not behave in the expected manner, this can further the sense of frustration and anger towards America. The opinions of the Arab street in the surveyed countries have also shown that there is a potential light at the end of the tunnel—43% of respondents overall still believe that a two-state solution is possible, and in countries like Egypt and Jordan, this percentage nearly reaches 50%.

Only time will tell if these shifts in Arab public opinion toward the United States and the rest of the West are a temporary spike in anger at a time when this has become the most pressing popular issue in the region, or whether these attitudes will harden and represent a more permanent shift. Two factors will likely play important roles in the future trajectory of Arab public opinion toward the Gaza War and the West.

The first factor is the duration of the war. Images of dead and wounded Palestinian men, women, and children are now ubiquitous in Arab traditional and social media. In the case of a protracted war, it is possible some Arabs will grow weary of the conflict and turn to other issues, but a significant shift away from the conflict is difficult to imagine given the intensity of media coverage in the Arab world. The longer the conflict lasts and the longer these images flood Arab popular consciousness, the more likely it is that Arab anger will persist or even grow far past the duration of the current conflict.

The second factor that will help shape Arab attitudes about the war and the West is the trajectory that the conflict takes. In other words, the actions of the Israeli government and its Western backers will be critical in how this war is framed in the Arab world after its conclusion. Currently, fears of a mass displacement of both Gazan and West Bank Palestinians to Egypt, Jordan, or elsewhere are likewise a frequent point of media conversation. If Israel attempts to shift portions of the Palestinian population out of Gaza or creates a long-term occupation in Gaza, it will further inflame Arab opinion on the conflict and deepen resentment toward the West.

It seems likely that future Arab attitudes towards Iran, China, and Russia will largely follow the same logic. Rather than being driven by any particular actions or state messaging from these actors, this bump is probably being shaped by the perception that these countries are “enemies of my enemy” as outspoken opponents of the West, each in their own way. How lasting this favorability bonus will be likewisedepends on the duration and course of the conflict.

Finally, it is important to assess what the prevailing negative Arab attitudes toward the United States means for the relations between the United States and these populations’ respective governments, and whether Arab opinion “on the street” could pressure Arab governments to curtail relations and cooperation with Washington. While it is unlikely that there will be any profound breaks in relations between the United States and friendly Arab governments over this conflict, it will be increasingly uncomfortable over time for Arab governments to publicly engage with U.S. officials if the conflict persists or takes a more deleterious turn for the population in Gaza. It will be important to assess the depth of Arab anger toward the West and understand if and when there is a point in time where Arab attitudes toward the United States have soured so badly that the United States is no longer viewed as a necessary evil in the region but is instead no longer welcome by most.

Methodological Note

The survey included comprehensive national samples of 500 interviews in each country. All interviews were conducted during the period from October 17-29, 2023, through face-to-face (CAPI) interviews in Iraq and Syria and telephone interviews in other countries.